‘Don's Dawn’, from New York Eye and Ear Control (1964), by Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, John Tchicai, Roswell Rudd, Gary Peacock & Sunny Murray.

Courtesy of Juno Records.

Pajari Räsänen's weblog in English. A personal notebook of sorts.

‘Don's Dawn’, from New York Eye and Ear Control (1964), by Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, John Tchicai, Roswell Rudd, Gary Peacock & Sunny Murray.

Courtesy of Juno Records.

Intolerable: reading about other men's despair makes my despair more tolerable.

Great men's great despair against my measly little one.

A "loneliness that is experienced together" (Blanchot). And the observation, still by Blanchot, that whoever uses the phrase "I am alone" is necessarily comical.

I have no idea who first "used" the line "this loneliness won't leave me alone", but at least Otis Redding used it, before many others, such as the band Portishead.

Depressive realism plus narcissism: I don't deserve myself.

A moment later, taking up Kafka's diaries, I come across these two subsequent notes ("Das dritte Oktavheft", Nov. 21, 1917):

Das Böse weiß vom Guten, aber das Gute vom Bösen nicht.

Selbsterkenntnis hat nur das Böse.

After another moment, this one (Jan. 14, 1918):

Es gibt nur zweierlei: Wahrheit und Lüge.

Wahrheit ist unteilbar, kann sich also selbst nicht erkennen; wer sie erkennen will, muß Lüge sein.

Emmanuel Levinas dismisses the metaphor of rootedness:

L’homme, après tout, n’est pas un arbre et l’humanité n’est pas une forêt.↓

For Levinas, the “notion of Israel” is not coextensive with the historical, geografical or geopolitical borders of the state of Israel. His “essays on judaism” actually provide a strong argument against the political misuse of the name of Israel. For judaism, in contrast to what a certain “great contemporary philosopher” teaches about rootedness and the world, it is not the “houses, temples and bridges” that let the world become intelligible, but the face of the other;↓ to put it briefly, being-with-others rather than being-in-the-world.

L’homme commence dans le désert où il habite des tentes, où il adore Dieu dans un temple qui se transporte.↓

In the Talmud, Levinas maintains, the notion of Israel remains separate from all historical, national, local and racial determinations. This separation implies a freedom with regard to all landscapes and architectural monuments, all “these heavy and sedentary things that one is tempted to prefer to human beings”. With respect to this freedom, rootedness (enracinement) becomes secondary, compared with other forms of fidelity and responsibility; other more vast horizons than the village and a given human society emerge for the vision that presupposes a conscious engagement.↓

Le judaïsme est une extrême conscience.↓

The extreme nature of this conscience – both consciousness and moral conscience – is, to use words that Derrida might use to counter-sign Levinas, a confrontation with aporia, a desert kind of pathlessness, and the undecidable.

Même lorsque l’acte est raisonnable, lorsque l’acte est juste, il comporte une violence. […] Voilà aussi pourquoi l’engagement nécessaire est si difficile au juif, voilà pourquoi le juif ne peut pas s’engager sans se désengager aussitôt, voilà pourquoi il lui reste toujours cet arrière-goût de violence, même quand il s’engage pour une cause juste […]↓

« Alors que la vie ordinaire précède le récit que l’on peut en faire, j’ai parié qu’une certaine vie n’est ni antérieure, ni extérieure á écrire » — Roger Laporte

A multivalent, multicultural society should not be structured like a honeycomb whose cells are isolated one against the other, so that none of the individual or group-related values gets challenged, but a society with a multitude of values that are subject to debate and exchange, a multitude of cultures that are exposed to the influence of each other, a society that is subjected to nothing else than the radical idea of a “democracy to come”.

"Muqarnas are stalactite or honeycomb ornament that adorn cupolas or corbels of a building." A Year in Fez — The photo was found through an image search with the terms arabesque honeycomb commons

"... l'amitié, elle aussi, tend à devenir totalitaire." (Jean-Paul Sartre)

This tendency towards a "totalitarianism" or totalisation, even in questions of friendship, is something I don't quite approve of in Sartre. I don't think he's joking in his rather brutal reply to Camus.

An account — travelogue — of my recent sentimental journey through Schwaben and Schwarzwald was published in the online journal Mustekala on 12-12-12, both in Finnish and in English, as slightly different versions.

« Aucun oiseau n’a le cœur de chanter dans un buisson de questions. » (René Char)

»Kein Vogel, der singen möchte in einem Gebüsche von Fragen.« (Nachgedichtet von Paul Celan)

“No bird has the heart to sing in a thicket of questions.” (Translated by Susan Sontag)

"'Schreiben als Form des Gebets': An Impossible Form of Apostrophe? : 'P. S' on a fragment by Kafka as adopted by Celan." My article with that impossible title is also online now (PDF, 6 MB). It appeared five years ago in the volume edited by Päivi Mehtonen, Illuminating Darkness: Approaches to Obscurity and Nothingness in Literature (Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 2007), 187–207.

The article contains, as its most important ingredient, my reading of Celan's poem "Wirk nicht voraus", different from another discussion of the same poem in my doctoral dissertation (see below) and more detailed.

*Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Rousseau juge de Jean-Jaques [sic]. Dialogues, texte présenté par Michel Foucault (Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1962), 156.

Counter-figures: An Essay on Antimetaphoric Resistance. Paul Celan's Poetry and Poetics at the Limits of Figurality (diss., 2007, 398 pp.) is now available also via Google Books, free of charge.

This video gets stuck at 1m56s at its original address; let's see if it streams better as embedded... It appears to do so!

I was just listening to Peeter Uuskyla and Peter Brötzmann's wonderful duo album, Born Broke, and went YouTubeing for more of Uuskyla's drumming.

Beauty itself is either

The good itself is either

But why "either – or"? Why not "both – and"?

Cf. René Magritte's painting Ceci n'est pas une pomme

.

The font is Type-Ra by Junkohanhero.

This quote

from Magritte was inspired by the exhibition – which I've so far only read about – Text Art – Poetry for the Eye in Tampere, Finland.

See also my blog in Finnish.

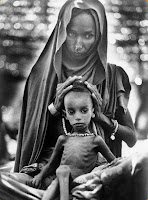

In the very heart of Christianity, not only a humiliated prophet but a suffering god, a wounded god which sounds like an oxymoron; not only nativity, the becoming of flesh, but also mortality, flesh in its most vulnerable unbecomingness.

Unfortunately, I have no copyright information on this photograph; it is copied from another blog, A Buddhist Catholic, and slightly cropped to remove a thin frame. – See also artworks by Grünewald, Congdon, etc. etc.

Yet, in a polyvalent society and multicultural world, discretion in image-making should be an ethical prerequisite...

Le poème moderne est d'autant moins la forme sensible de l'Idée que, bien plutôt, c'est le sensible qui se présente comme nostalgie subsistante, et impuissante, de l'idée poétique. – Alain Badiou, Petit manuel d'inesthétique (Paris: Seuil, 1998), 38.

Quand on lit trop vite ou trop doucement on n'entend rien.

– Pascal

This is the motto of Paul de Man's Allegories of Reading and it certainly applies to reading de Man himself, too. But I find myself enjoying the effort more than before.

Physically upright but morally crooked – a strategic phrase to unlink a systematic chain of unwarranted or dubious connections – not a metaphor, or a pair of metaphors, but a counter-metaphor, a backward twist, reductio ad absurdum.

. . .

Yet, "physically upright" was never just "physical", pure and simple, in the first place. "Upright" was never an exclusively "physical" concept, and there is no such thing as an exclusively "physical" concept. This is not to say that "uprightness" was always already "moral", but rather that the perception of "something upright" would not take place without "theory", or "ideas" and concepts. "The visible is pregnant with the invisible" (Merleau-Ponty, positively commenting on Heidegger's refutation of the concept of metaphor).

Daß es wirklich einfache Bedeutungen gibt, lehrt das unzweifelhafte Beispiel Etwas. Das Vostellungserlebnis, das sich im Verständnis des Wortes vollzieht, ist sicherlich komponiert, die Bedeutung ist aber ohne jeden Schatten von Zusammensetzung.

– Edmund Husserl, Logische Untersuchungen. II/1: Untersuchungen zur Phänomenologie und Theorie der Erkenntnis, siebte Auflage (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, 1993), 296.

I am marking this passage just because I find it powerful and fascinating (as I see it, intellectual insight need not be severed from aesthetic pleasure), and a sort of condensation of Husserl's critique of psychologism.

[...] le prochain, mon frère, l’homme, infiniment moins autre que l’absolument autre, est, en un certain sense, plus autre que Dieu : pour obtenir son pardon le jour du Kippour, je dois au préalable obtenir qu’il s’apaise.

– Levinas, Quatre lectures talmudiques (Paris: Minuit, cop. 1968, repr. 2002), 36-37.

An approximation in English: My fellow man, my brother (yes, it is a good question to ask: why always or most often in Levinas the masculine gender, why "brother" and not "sister"?), the human being, infinitely "less other" than the absolutely other, is, in a certain sense, "more other" than God. To obtain God's forgiveness on the Day of Atonement, it is required that we are at peace with our fellow man.

Doesn't this mean that the "cultivation of intimacy" – whose preëminent figure is the intimacy with God, in prayer, for instance, or the silent negotiation with one's conscience – is always, always already interrupted by "a third party"?

Reading – very slowly and too absent-mindedly – Husserl's Logische Untersuchungen, the two verses that end the following stanza of Marvell's "The Garden" came to my mind, as they often do:

Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less,

Withdraws into its happiness :

The mind, that ocean where each kind

Does straight its own resemblance find ;

Yet it creates, transcending these,

Far other worlds, and other seas ;

Annihilating all that's made

To a green thought in a green shade.

Green is not green – the green, namely greenness, being-green, is not itself "coloured" – a Heideggerean reminder. The green of all greens is not green. Colour is colourless.

Helen Frankenthaler, A Green Thought in a Green Shade (1981)

An abstract expressionism that seeks for the essence of colour – say, green, the green of green, the green-ness of green – is therefore a splendid failure.

Emphasis on "splendid".

* * *

A green thought must inhabit – take repose in – a green shade, "withdraw into its happiness" there, and acknowledge its constitutive différance.

* * *

Every green thought that takes repose in a green shade, every representation of "green", is an allegory of "green".

See the article "It's 55 percent and wrapped in roadkill, is this the world's most 'shocking' beer?" (msnbc.com) for more information about the image. A quote:

The decision to wrap the bottle in a dead animal was taken to indicate how special the beer was, blending brewing, taxidermy and "art."

– – –*

I wouldn't mind being turned into a coffee pot warmer after my death, but nobody asked the squirrel. I have mixed feelings about this kind of recycling: I think respecting a dead body is not completely irrational, and it doesn't seem to me that the brewery actually pays respect to the poor beasts (whether they manage to indicate the specialty of the "beer" with this gimmick is another question).

It's all the same shit these days. It's all raw matter, indifferent when it's dead. But in a sustainable culture, even shit deserves respect: fæces will be recycled as compost and thereby turned into "humanure", a soil amendment – earth to earth – and not just flushed away with precious fresh water.

* I will update this post later, since there's a lot to say about "materialist" indifference.

L'homme est l'être qui ne peut sortir de soi, qui ne connaît les autres qu'en soi, et, en disant le contraire, ment.

Man is the creature that cannot emerge from himself, that knows his fellows only in himself; when he asserts the contrary, he is lying.*

Paradoxically or not, acknowledging this quasi-solipsistic principle is a prerequisite of an ethical relation to other people, other minds, hearts and bodies. Another paradox is that we can learn to acknowledge this truth – about a lie – through fiction, itself a sort of lie. Literature constitutes the type of lying that, while pretending to penetrate the surface of another man's being, or while, explicitly or implicitly, manifesting different variations of this theme of penetration (or non-penetration), also maintains its status as a "lie" of sorts, an illusion "conscious" of itself (this "consciousness" is not "someone's" consciousness, and thus not really a consciousness in the first place; it can also be a manifestation in spite of itself, "ultra-subjective").

* Marcel Proust, Albertine disparue (Paris: Gallimard, 1999), 34. Trans. C.K. Scott-Moncrieff.

Circumcision, brit milah, at once both incision and excision: a sign, symbol, sumbolon, token of participation, a letter avant la lettre, a word drawn (like you draw blood, and not only “like”) from an infant.

(A marginal note to the chapter on "The Tropic of Circumcision".)

"Taking centre stage is Superman with his distinctive red cape and blue suit. To the left is Santa Claus and to the right Ronald McDonald, the mascot of the fast-food giant McDonalds, and the Joker also makes an appearance." – Emily Allen, Daily Mail Online Tues. 21 June, 2011

The article does not mention the fact that the "red flag" carried by the soldiers has been turned into Stars and Stripes. A "liberation" replaced by another "liberation"...

I guess many people would "read" in(to) this graffiti a celebration of the freedom to go to MacDonald's. I would rather "read" in(to) it a celebration of another freedom: the freedom to be ambiguous. Not political and economic "liberation", that is, but an artistic liberation – more constitutive for democracy than the introduction of "free" market economy, as I see it.

Thinking is not just an activity, but a passion – a passion for that which is and remains to be thought.

Philosophy, as passion, is not – perhaps not – essentially mastery, but a vulnerability.

* * *

You could replace "philosophy", above, with "philology" – see Werner Hamacher's and Thomas Schestag's recent "theses" on philology – and, perhaps, "thinking" with "reading" and "thought" with "read" (that which "is and remains to be read" is "something" that certainly "is and remains to be thought", but some people might pretend that "that which is and remains to be thought" is not always something "to be read").

I am re-reading Octavio Paz's Children of the Mire, and the following in it:

Critical passion: excessive, impassioned love of criticism and its precise devices for disconstructions,* but also criticism in love with its object, ...

* "Disconstructions": I don't have the Spanish original at hand (while, on the other hand, the English translation is rather an English version, constituting Paz's Norton Lectures of 1972), but it would by no means be far-fetched to read "deconstructions", provided that we forget, for a moment, that deconstruction is not a device, let alone a set of "deconstructions" as a set of "devices".

…Words, English words, are full of echoes, of memories, of associations. They have been out and about, on people's lips, in their houses, in the streets, in the fields, for so many centuries. And that is one of the chief difficulties in writing them today – that they are stored with other meanings, with other memories, and they have contracted so many famous marriages in the past. The splendid word "incarnadine," for example – who can use that without remembering "multitudinous seas"? In the old days, of course, when English was a new language, writers could invent new words and use them. Nowadays it is easy enough to invent new words – they spring to the lips whenever we see a new sight or feel a new sensation – but we cannot use them because the English language is old. You cannot use a brand new word in an old language because of the very obvious yet always mysterious fact that a word is not a single and separate entity, but part of other words. Indeed it is not a word until it is part of a sentence. Words belong to each other, although, of course, only a great poet knows that the word "incarnadine" belongs to "multitudinous seas." To combine new words with old words is fatal to the constitution of the sentence. In order to use new words properly you would have to invent a whole new language; and that, though no doubt we shall come to it, is not at the moment our business. Our business is to see what we can do with the old English language as it is. How can we combine the old words in new orders so that they survive, so that they create beauty, so that they tell the truth? That is the question.

And the person who could answer that question would deserve whatever crown of glory the world has to offer. Think what it would mean if you could teach, or if you could learn the art of writing. Why, every book, every newspaper you'd pick up, would tell the truth, or create beauty. But there is, it would appear, some obstacle in the way, some hindrance to the teaching of words. For though at this moment at least a hundred professors are lecturing on the literature of the past, at least a thousand critics are reviewing the literature of the present, and hundreds upon hundreds of young men and women are passing examinations in English literature with the utmost credit, still – do we write better, do we read better than we read and wrote four hundred years ago when we were un-lectured, un-criticized, untaught? Is our modern Georgian literature a patch on the Elizabethan? Well, where then are we to lay the blame? Not on our professors; not on our reviewers; not on our writers; but on words. It is words that are to blame. They are the wildest, freest, most irresponsible, most un-teachable of all things. Of course, you can catch them and sort them and place them in alphabetical order in dictionaries. But words do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. If you want proof of this, consider how often in moments of emotion when we most need words we find none. Yet there is the dictionary; there at our disposal are some half-a-million words all in alphabetical order. But can we use them? No, because words do not live in dictionaries, they live in the mind. Look once more at the dictionary. There beyond a doubt lie plays more splendid than Antony and Cleopatra; poems lovelier than the Ode to a Nightingale; novels beside which Pride and Prejudice or David Copperfield are the crude bunglings of amateurs. It is only a question of finding the right words and putting them in the right order. But we cannot do it because they do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. And how do they live in the mind? Variously and strangely, much as human beings live, ranging hither and thither, falling in love, and mating together. It is true that they are much less bound by ceremony and convention than we are. Royal words mate with commoners. English words marry French words, German words, Indian words, Negro words, if they have a fancy. Indeed, the less we enquire into the past of our dear Mother English the better it will be for that lady's reputation. For she has gone a-roving, a-roving fair maid.

Thus to lay down any laws for such irreclaimable vagabonds is worse than useless. A few trifling rules of grammar and spelling is all the constraint we can put on them. All we can say about them, as we peer at them over the edge of that deep, dark and only fitfully illuminated cavern in which they live – the mind – all we can say about them is that they seem to like people to think before they use them, and to feel before they use them, but to think and feel not about them, but about something different. They are highly sensitive, easily made self-conscious. They do not like to have their purity or their impurity discussed. If you start a Society for Pure English, they will show their resentment by starting another for impure English – hence the unnatural violence of much modern speech; it is a protest against the puritans. They are highly democratic, too; they believe that one word is as good as another; uneducated words are as good as educated words, uncultivated words as good as cultivated words, there are no ranks or titles in their society. Nor do they like being lifted out on the point of a pen and examined separately. They hang together, in sentences, paragraphs, sometimes for whole pages at a time. They hate being useful; they hate making money; they hate being lectured about in public. In short, they hate anything that stamps them with one meaning or confines them to one attitude, for it is their nature to change.

Perhaps that is their most striking peculiarity – their need of change. It is because the truth they try to catch is many-sided, and they convey it by being many-sided, flashing first this way, then that. Thus they mean one thing to one person, another thing to another person; they are unintelligible to one generation, plain as a pikestaff to the next. And it is because of this complexity, this power to mean different things to different people, that they survive. Perhaps then one reason why we have no great poet, novelist or critic writing today is that we refuse to allow words their liberty. We pin them down to one meaning, their useful meaning, the meaning which makes us catch the train, the meaning which makes us pass the examination…

I am trying to think about the most extreme of all typologies:* the relation between Abraham's sacrifice and its "antitype" – or, in other words – the sacrifice of Isaac and its "antitype".

I came across a "scandalon" that is, I believe, radically different from the consequence of José Saramago's great novel The Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The scandalon I ended up contemplating resembles, as an extreme scandalon, many others in the Bible, both Old and New Testament; episodes that show God himself showing hesitation, remorse, or other strangely – or perhaps just apparently – "human" characteristics, episodes that Jacques Derrida singled out in several of his writings dealing with, for example, the relation between religion and "the origin of literature".

I would refer to this extreme scandalon by the words God's suffering or the "passion" of God; but it is not only the Son's passion. If we take the typology "seriously enough" (Kierkegaard would probably detest the assumption that there can be an "enough" in this "case"), we cannot overrule the suffering of the Father – a moment of mad suffering, a mad passion, incomprehensible, impossible.

The mystics say that God's drunkenness is infinitely more sober than human sobriety, and that God's folly is infinitely wiser than human wisdom.

I am probably not the first to have thought – or tried to think – along these lines, about this most extreme of all typologies. In any case, I am not a theologian, but rather one of the so-called "free thinkers", one who tries to commit his freedom to think the unthinkable. An agnostic of sorts, I guess. (I'm not sure if I could call myself an "atheist", because the atheists that I know would probably refuse to even think about such a theme as "God's suffering". Some of them might even deny that Saramago, for example, is a real atheist.)

P.S. This blog post probably just reveals a shameful lack of erudition, but I'll expose myself to this threat. Please comment.

__

* The ellipsis is intentional: I would not say "the most extreme case", "the most extreme example", for example. It is not just an "example" among others.

DICHTERLOS

Für alle muß vor Freuden

Mein treues Herze glühn,

Für alle muß ich leiden,

Für alle muß ich blühn,

Und wenn die Blüten Früchte haben,

Da haben sie mich längst begraben.

Could not find a translation... but will edit this post later and add one, in case I find one. If you know one or have one, feel free to comment.

In any case – can we avoid the pun? A poet's lot – fate, destiny, Dichterlos – is, or will be, a world without the poet, dichterlos. A poet's lot is a poem, eine eine-für-alle-Allegorie, poetless.

A poet's time is out of joint (los).

* * *

"Dichterlos" was set to music by Othmar Schoeck (Elegie Op. 36/23).

or,

... Don't you know that you can count me out – in ...

I got a very prompt and apt comment to the previous (scroll down, if you will – or try to live & read without the illusion of "linearity") post in Facebook, and would like to add my friend Gary's comment as such, with my own reply, in the form of a screenshot – *click* to view it full-size –

But on a second thought – see my previous post, "Street Fighting Dressman[n]" – maybe we "liberal democrats"* should just cherish the fact that no single political tendency can harness truly "popular music"! Neither the left, nor the right. Popular music is "democratic" to the point of utter disobedience and disloyalty – and maybe we should just affirm that? Maybe we should just affirm the fact that "Street Fighting Man" and "Sympathy for the Devil" remain the songs that cause goose bumps, even when we smirk at their commercial application? Maybe we should even affirm the scribbling of "Rock the Casbah" on the side of a bomb meant to – well, "rock" the casbah – you do know how the soldiers scream "let's rock'n'roll" when they go out to kill?

"I know it's only rock & roll, but I like it" – and hate it – and...

* "Liberal democrats"? What was I thinking? — I tend to describe my political position as "red, gold and green", "gold" being — not money, wealth or capital, but — an ingredient of what I would call aesthetico-ethical dis-engagement...

»In one of the campfire scenes late in the 2007 documentary Joe Strummer: The Future Is Unwritten, a Granada friend states that Strummer wept when he heard that the phrase "Rock the Casbah" was written on an American bomb that was to be detonated on Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War« (Wikipedia, "Rock the Casbah").

Little room left for revolution in rock & roll. A form of music that can be appropriated, violently or not, by the most conservative circles, often for political and/or commercial ends.

Yet, maybe there remains hope for a revolution that makes room for rock & roll and Joe Strummer's tears – pop music is, anyway, popular music, the people's music, even if avant garde aficionado's like me tend to prefer forms that are more inappropriable – inappropriable, not by the masses, but by the conservative elite.

Can't help but love the song. To the brink of weeping, myself.

Ernst Meister: "Viele..." (from Sage vom Ganzen den Satz, 1972)

VieleTranslated by Tatjana M. Warren with Robert L. Crosson:

haben keine

Sprache.

Wär ich nicht selbst

satt von Elend,

ich bewegte

die Zunge nicht.

Many

have no

speech.

Had I not

my fill of misery,

I would not

move my tongue.*

Good verse is sometimes good because it provokes certain questions that are almost objections. An unquenchable thirst for the words of a silent partner.

One's "fill of misery" – would it not rather render utterly speechless? Or is the "fill" a saturation of such a sort that it comes after all the miseries, a deluge of misery that leaves nothing but the speech – words totally transformed in their function and depth – or depthlessness?

.........

How to speak for the sake of the other who has no speech, without pretending to speak for the other (or: in place of the other – you cannot – even if you cannot avoid it, either)? A question – perhaps without an answer – that remains crucial for democracy.

__

* Quoted from Michael Mantler's website:

And what, said I, well he said, when a train was going by at a terrific pace and we waved a hat the engine driver could make a bell quite carelessly go ting ting ting, the way anybody playing at a thing could do, it was not if you know what I mean professional he said.*

Battles are named because there have been hills which have made a hill in a battle.**

Dykman et al. (1989) argued that, although depressive people make more accurate judgments about having no control in situations where in fact they have no control, they also believe they have no control when in fact they do; and so their perceptions are not more accurate overall.

Die Philosophie ist eigentlich Heimweh, ein Trieb überall zu Hause zu Sein.

As apothecaries we make new mixtures everyday, pour out of one vessel into another; and as those old Romans robbed all the cities of the world, to set out their bad-sited Rome, we skim off the cream of other men's wits, pick the choice flowers of their tilled gardens to set out our own sterile plots. Castrant alios ut libros suos per se graciles alieno adipe suffarciant (so Jovius inveighs.) They lard their lean books with the fat of others' works. Ineruditi fures, &c. A fault that every writer finds, as I do now, and yet faulty themselves, Trium literarum homines, all thieves; they pilfer out of old writers to stuff up their new comments, scrape Ennius' dunghills, and out of Democritus' pit, as I have done. By which means it comes to pass, "that not only libraries and shops are full of our putrid papers, but every close-stool and jakes," Scribunt carmina quae legunt cacantes; they serve to put under pies, to lap spice in, and keep roast meat from burning. "With us in France," saith Scaliger, "every man hath liberty to write, but few ability." "Heretofore learning was graced by judicious scholars, but now noble sciences are vilified by base and illiterate scribblers," that either write for vainglory, need, to get money, or as Parasites to flatter and collogue with some great men, they put cut burras, quisquiliasque ineptiasque. Amongst so many thousand authors you shall scarce find one, by reading of whom you shall be any whit better, but rather much worse, quibus inficitur potius, quam perficitur, by which he is rather infected than any way perfected. [...] So that oftentimes it falls out (which Callimachus taxed of old) a great book is a great mischief. Cardan finds fault with Frenchmen and Germans, for their scribbling to no purpose, non inquit ab edendo deterreo, modo novum aliquid inveniant, he doth not bar them to write, so that it be some new invention of their own; but we weave the same web still, twist the same rope again and again; or if it be a new invention, 'tis but some bauble or toy which idle fellows write, for as idle fellows to read, and who so cannot invent?

Point d’ironie n° 37 by Ed Ruscha at agnès b., rue du Jour, Paris. Sculpture by Jen-chri.

Plusieurs raisons ont été avancées pour expliquer le manque de succès du point d'ironie en tant que signe de ponctuation :

* Les signes comme le point d'interrogation ou le point d'exclamation servent généralement à retranscrire la façon dont est ponctuée la phrase à l'oral. Or, une phrase ironique n'est pas forcément ponctuée d'une certaine façon. Parfois, seul le contexte permet de la reconnaître comme telle. D'ailleurs, les personnes qui se veulent ironiques jouent souvent sur l'ambiguïté. [C'est moi qui souligne, P.R.]

Wenn denn nun gefragt wird : Leben wir jetzt in einem aufgeklärten Zeitalter ? so ist die Antwort : Nein, aber wohl in einem Zeitalter der Aufklärung. [If it is now asked, “Do we presently live in an enlightened age?” the answer is, “No, but we do live in an age of enlightenment.”]Enlightenment, not "being enlightened" but "being in the process of enlightening [Aufklärung]" or "becoming enlightened," is reason's constant readiness for critical self-examination – a constant crisis and not a status quo.

Online texts:

German original, Immanuel Kant, "Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?" (1783) – www.prometheusonline.de.

English translation, by H.B. Hisbet (?), "An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?" (1784)

You are perhaps aware that the oldest manuscripts of the Gospel of Mark – the oldest canonical gospel – ended after 16:8 where the women discover Jesus' tomb to be empty and leave it in distress. "And they told ... no one anything; for they were afraid" (who is narrating this?)Thank you J. B., I hope you don't mind me quoting you.